We all have different ideas of what a palate cleanser is. In my case, specifically this past week where I’ve been strangely obsessed with French crime and heist films from the 1950s and 1960s, perhaps in preparation of a different newsletter (coming soon, I hope), I found myself in need of watching something different. Staying in the thriller genre, I wandered on the Criterion Channel, and stumbled upon their wonderful collection of “Surveillance Cinema”, picking a film that has been on my watchlist for longer than I can remember: Francis Ford Coppola’s The Conversation from 1974.

A film sandwiched in between two masterpieces (only The Godfather and The Godfather II), it was a true passion project that was made on a shoestring budget and revealed, perhaps, the true intent of his body of work: the effect of power and control on the soul.

Always a Coppola fan (yes, even the chaotic Megalopolis), I expected to like it. I did not expect to like it as much as I did. A true slap in the face that is as relevant today as it was during Watergate, The Conversation is a deeply paranoid, deeply personal film about privacy, or the lack thereof in our increasingly modern, overly-surveilled world.

Coppola follows Harry Caul (played with much restraint and agonizing guilt by the great Gene Hackman), a surveillance expert as he conducts his latest mission: to record a conversation between two people, seemingly forbidden lovers, in a crowded park in San Francisco during lunch hour. Caul and his assistant Stan (John Cazale, a screen appearance that always induces bittersweet feelings) use a variety of tools and techniques to capture the two voices: sniper-like long-range microphones, portable recorders hidden in a murky shopping bag and carried by a lurking ex-cop, clarifying technology to clean out the noise and diegetic music from the physical space.

Caul concocts, with great effort and detail, a “nice fat recording” (in his words) he can deliver to his employer, an unnamed “director” of what seems to be a large, powerful corporation. What for? Stan asks. Caul says he doesn’t care, but he in fact cares quite a lot. A reluctant responsibility he cannot escape from, devout Catholic and all.

As he pieces sounds together to create the perfect aural image, Caul starts to understand that the repercussions of his work could be severe for the people recorded (an unfortunate effect that happened following a previous assignment, and resulted in the murder of three people: something Caul never recovered from). He grows obsessed with the recording: listening to it over and over again, attempting to deduce meaning, intent, fear.

In his paranoid, repressed lonesome, Harry Caul cannot separate his guilt from his profession, and inserts himself in what he believes to be a plot aimed against the two young lovers. Along the way, Caul interacts with a brilliant cast of characters (amongst others, a very young Harrison Ford and a moving Teri Garr), often putting him face to face with his own contradictions, his own inabilities, and his growing fears.

Repeatedly framed behind glass, cages, and in tight, confined spaces, Gene Hackman’s stoic, self-loathing physicality complements Bill Butler’s cinematography here, igniting in the audience a real sense of claustrophobia and imprisonment. Especially when paired with Caul’s guilt-driven catholicism, the isolation of the character is telling of his inability to connect with others, and to read social situations. It’s no accident that the man who steals others’ privacy is so protective of his own. As a result, he is often the “victim” of invasions of privacy himself: his landlord owning a key to his apartment, a neighbor knowing of his birthday, a lover asking too many questions, a competitor taping him “as a joke”. Ultimately, it’s his inability to read, or “hear”, the situation that descends him into a moral and mental point of no return.

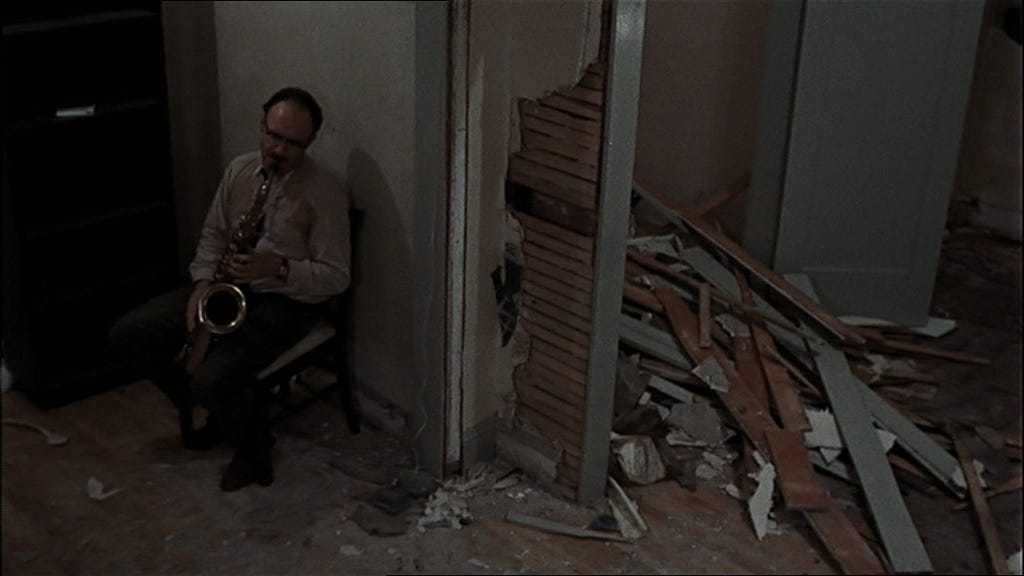

With an opening sequence that is truly memorable (a long and slow zoom in the park), the cinematography is significant for the atmosphere and the meaning of the film, but it is truly a film about sound, and specifically, the repetition of sound (editing and sound editing were both done by the incomparable Walter Murch). With a genius score by David Shire and beautiful jazz on the saxophone as Caul plays alone in his apartment, music is everywhere, and it is always meticulously placed, allowing for small moments of respite in an otherwise chaotic, oversaturated soundscape.

The sounds you hear, the sounds you want to hear, the sounds you don’t want to hear. In one of the strongest scenes, the juxtaposition and culmination of Caul’s obsession and guilt, we the audience start to truly doubt what we hear. What we see and what we hear come, after all, from Caul’s distorted point of view which grows increasingly unreliable. The guilt, to him, is completely paralyzing, and when he thinks he overhears a murder in the next room, he is incapable of moving. He simply cannot do anything but hide under the covers.

It is only at the end that the audience (and Caul himself) is rewarded: we only saw what he thought he saw. But it is not the reality - not the objective reality, anyway. Caul has made assumptions and has acted on them, shielding him along the way from the truth. The result is still a tragedy, still a terrible truth, one that will keep haunting him, but not in the way he expected.

Here lies the genius of Coppola’s film: no matter how much we want to believe in something, and no matter how horrible that thing might be, the reality is often way, way worse - and it’s impossible to bend it.

In the midst of it all, there is nothing else left to do than to relinquish control completely. In Caul’s case, that means playing his saxophone, alone, in his torn-up apartment.

Further reading

Two great reflections I found during my research: a study of Objective and Subjective Reality in the film and an essay from the BFI following the release of the film: a rare and untainted point of view on a young, promising Coppola, who still had his entire career in front of him.

Further watching

If this is up your alley, consider watching these:

Rear Window, Alfred Hitchcock (1954): if this is obsessed with sound, Rear Window is obsessed with image.

All the President’s Men, Alan J. Pakula (1976): the epitome of the Watergate thriller.

The Lives of Others, Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck (2006): when the personal creeps in.

September 5, Tim Fehlbaum (2024): while not a surveillance film, it masterfully deals with the technology of recording as well as the consequences of such recordings.

“I guess I’ll see you in the movies.”

I'd add BLOW OUT to films that fit this theme!

I've been drawing connections between the score for 'Severance' and The Conversation! It's such an amazing, influential score.